I’ve been bouncing around just at the edge of my 2016 presidential campaign overload limit, and the other night’s debate and associated post-debate blogging sent me right through it.

Yes, I was thrilled to see my preferred candidate (Hermione) outperform the other candidate (Wormtail), but all the post-debate analysis and gloating made me weary.

Then, I thought about the important issues facing this country, the ones that keep me up at night worrying for my kids, the ones that were not discussed in the debate, or if they were, only through buzzwords and hand waves, and I got depressed. Because there is precious little in the campaign that addresses them. (To be fair, Clinton’s platform touches on most of these, and Trump’s covers a few, though neither as clearly or candidly as I’d like.)

So, without further ado, I present my list of campaign issues I’d like to see discussed, live, in a debate. If you are a debate moderator from an alternate universe who has moved through an interdimensional portal to our universe, consider using some of these questions:

1.

How do we deal with the employment effects of rapid technological change? File the effects of globalization under the same category, because technological change is a driver of that as well. I like technology and am excited about its many positive possibilities, but you don’t have to be a “Luddite” to say that it has already eliminated a lot of jobs and will eliminate many more. History has shown us that whenever technology takes away work, it eventually gives it back, but I have two issues with that. First, it is certainly possible that “this time it’s different. Second, and more worrisome, history also shows that the time gap between killing jobs and creating new ones can be multigenerational. Furthermore, it’s not clear that the same people who had the old jobs will be able to perform the new ones, even if they were immediately available.

This is a setup for an extended period of immiseration for working people. And, by the way, don’t think you’ll be immune to this because you’re a professional or because you’re in STEM. Efficiency is coming to your workplace.

It’s a big deal.

I don’t have a fantastic solution to offer, but HRC’s platform, without framing the issue just as I have, does include the idea of major infrastructure reinvestment, which could cushion this effect.

Bonus: how important should work be? Should every able person have/need a job? Why or why not?

2.

Related to this is growing inequality. The technology is allowing fewer and fewer people to capture more and more surplus. Should we try to reverse that, and if so, how do we do so? Answering this means answering some very fundamental questions about what is fairness that I don’t think have been seriously broached.

Sanders built his campaign on this, and Clinton’s platform talks about economic justice, but certainly does not frame it so starkly.

What has been discussed, at least in the nerd blogosphere, are the deleterious effects of inequality: its (probably) corrosive effect on democracy as well as its challenge to the core belief that everyone gets a chance in America.

Do we try to reverse this or not, and if so, how?

3.

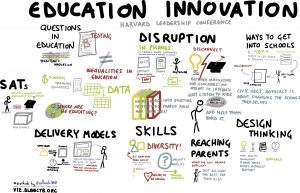

Speaking of chances, our public education system has been an important, perhaps the important engine of upward mobility in the US. What are we going to do to strengthen our education system so that it continues to improve and serve everyone? This is an issue that spans preschool to university. Why are we systematically trying to defund, dismantle, weaken, and privatize these institutions? Related, how have our experiments in making education more efficient been working? What have we learned from them?

4.

Justice. Is our society just and fair? Are we measuring it? Are we progressing? Are we counting everyone? Are people getting a fair shake? Is everyone getting equal treatment under the law?

I’m absolutely talking about racial justice here, but also gender, sexual orientation, economic, environmental, you name it.

If you think the current situation is just, how do you explain recent shootings, etc? If you think it is not just, how do you see fixing it? Top-down or bottom-up? What would you say to a large or even majority constituency that is less (or more) concerned about these issues than you yourself are?

5.

Climate change. What can be done about it at this point, and what are we willing to do? Related, given that we are probably already seeing the effects of climate change, what can be done to help those adversely effected, and should we be doing anything to help them? Who are the beneficiaries of climate change or the processes that contribute to climate change, and should we transfer wealth to benefit those harmed? Should the scope of these questions extend internationally?

6.

Rebuilding and protecting our physical infrastructure. I think both candidates actually agree on this, but I didn’t hear much about plans and scope. We have aging:

- electric

- rail

- natural gas

- telecom

- roads and bridges

- air traffic control

- airports

- water

- ports

- internet

What are we doing to modernize them, how much will it cost? What are the costs of not doing it? What are the barriers that are getting in the way of major upgrades of these infrastructures, and what are we going to do to overcome them?

Also, which of these can be hardened and protected, and at what cost? Should we attempt to do so?

7.

Military power. What is it for, what are its limits? How will you decide when and how to deploy military power? Defending the US at home is pretty straightforward, but defending military interests abroad is a bit more complex.

Do the candidates have established doctrines that they intend follow? What do they think is possible to accomplish with US military power and what is not? What will trigger US military engagement? Under what circumstances do we disengage from a conflict? What do you think of the US’s record in military adventures and do you think that tells you anything about the types of problems we should try to solve using the US military?

7-a. Bonus. What can we do to stop nuclear proliferation in DPRK? Compare and contrast Iran and DPRK and various containment strategies that might be deployed.